[this is part 2 about my time living on a farm in Vermont. Find part 1 here]

The Past

Magic Mountain is a story about a young engineer who graduates from school and prepares to enter the professional world. He travels to Switzerland, first, to visit his cousin, who has been kept in a sanatorium in order to heal from tuberculosis. I started reading it in 2019 and only got through a hundred pages. Again, in 2021, I got through another hundred. I’ve had four different copies in my life, one of them with each page I’ve read torn out and discarded to make the book easier to travel with. On Blood Mountain, I start over. I re-acquaint myself with Hans Castorp, the young engineer. I re-read his arrival and judgement of the isolated hospital, tucked high into the alps and away from the world. I re-read his plans for departure getting extended by a week, then another week, until an arduous hike leaves him gasping for air. After a consultation with the strange but enigmatic leader of the hospital, he is told he is showing early signs of TB, and is recommended to stay longer at the sanatorium. Now, as a patient rather than a visitor. Weeks turns into months, months into years. Castorp stops pretending to read the books he brought to study engineering, and his life slows to a glacial pace. He plays idly with lofty concepts. He spends hours sitting on his balcony wrapped in a blanket, and starts planning for events which are months away as if they’ll take place tomorrow. This, if he plans at all.

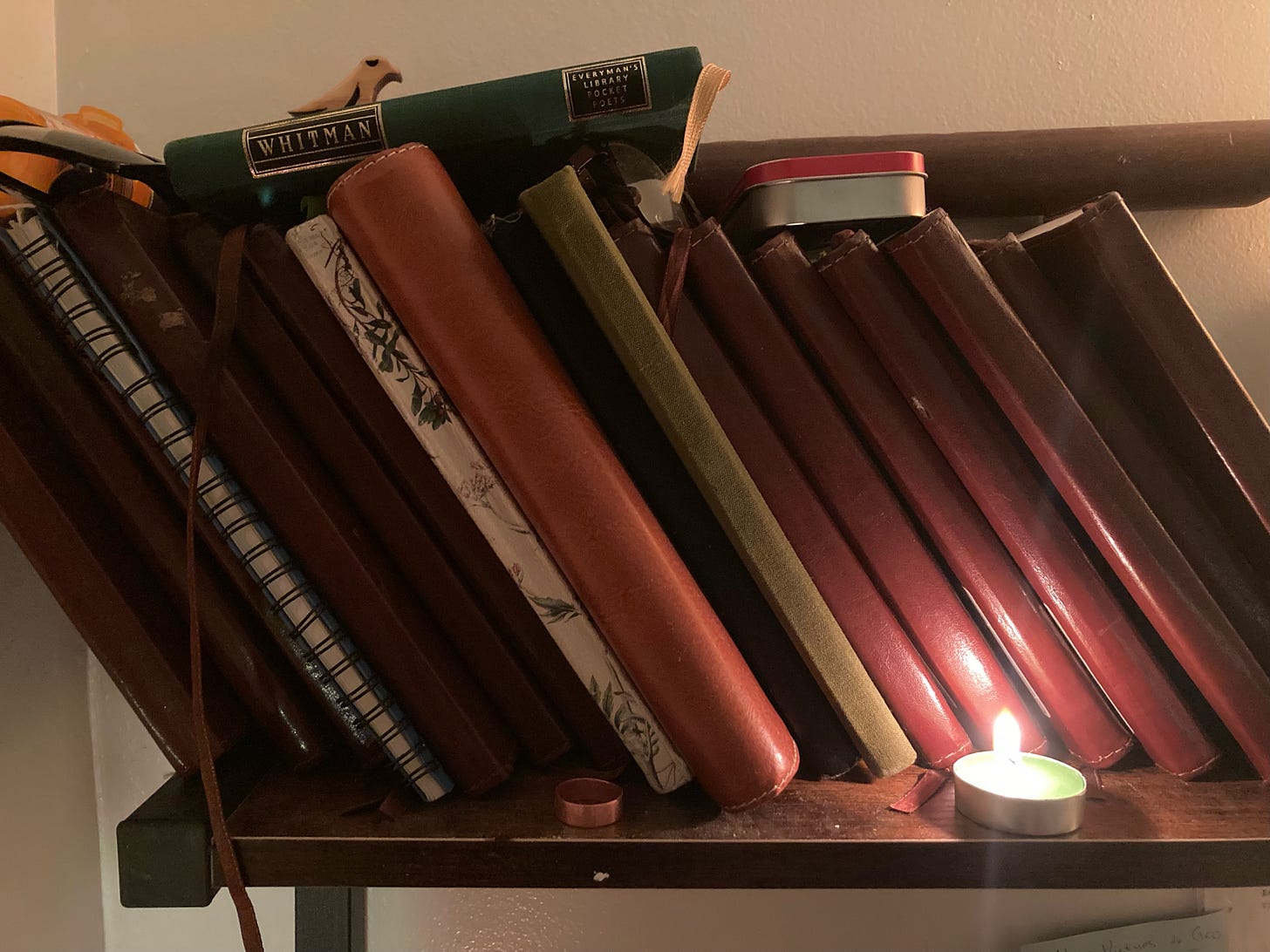

The next day Glenn leaves in his truck for Canada. He is going to pick up a sleigh from some Mennonites… or something. I don’t ask follow-ups. Katherina keeps to herself, and I continue the breakfast tradition. Bernie and Béla learn that I am now the one who feeds them, and they follow me up to the cabin each day on breaks. Hedy knows me well, and follows my command. Greta remains obstinate. For the first time in weeks, there is silence on Blood Mountain. One day, with my work finished early, I stare at the thirteen spines of seven years of journals.

The first begins in September of 2015. I had just moved to New York City and experienced a form of loneliness which Monroe, Connecticut couldn’t prepare me for. I missed my ex, I thought I was going to be a journalist. The passages are few and far between, and I fit a sloppy year into fifty pages of smeared ink. By my second journal I am nineteen, and the specter of loneliness and fear has become an indelible aspect of my character. It sounds melodramatic coming from a teenager, but at the tip of Blood Mountain I can spot an obsession with misery which, whether it was donned as a personality trait or signified something biological, had nonetheless morphed into the crisis I now faced.

If you’ve read this far, I ask you to bear with me. It can’t be very interesting to dwell on the psychological development of a twenty-something American male— we have so much of that which is so much better accomplished in the literary and cinematic and musical canon. What I’m getting towards, however, will hopefully be valuable. Because we can’t all afford therapy and because I suspect we all have the same overwhelming feeling that at some point, our own narratives outpaced us. That what started out intentionally has roistered into something outside of our control; an identity, untethered. A pathological monster within us, which serves as an ignoble Witness, dictating our beliefs and actions. How do we become a self? How does that self, then, come to control us?

I used to think that the most important and least teachable lesson was to be utterly oneself. That may be true— the first part certainly is— but the second part I am no longer sure of. I think it took me, personally, a thousand teachers to arrive at a place with a mere glimpse at that thing we call Fulfillment. Some sort of assurity of character and ethics on which I could rely, without being trapped by its limits. I am not one of those teachers, but here are the ideas of those I followed, I guess, distilled into a story about an old man on a mountain.

In my second journal I become obsessed with choosing success over happiness. Now, nearly a decade later, I’m still haunted by this battle. Each pleasant moment remains marred by the awning of what I could have achieved with that time; each success brings me closer to the fear that I may actually become successful, and it will not matter if I’m unhappy. I saw a self which was “empty + plastic + bad,” according to my journals. I longed for global suicide, beyond the charming punk version, and I continued to do so in that cabin. And yet at last, I cared. Cared about not caring, cared about this inner-directed hatred. That misery, back in 2016, began to drive itself towards artistic creation. (The jury on the merit of this is still out— it’s an ancient question, whether suffering for the sake of one’s art is cool, or fun, or okay. In America we reward those who do it in style, and pity those who do it unfavorably. Beautiful breakdowns have become valued at the societal level, if smirked at on the inter-personal.) In these pages from my time in New York I can watch the final vestiges of idealism snuffed, and in its place the beast of Depression entering. It quickly makes itself at home in the style of all my heroes before me. I watch in those pages as my consciousness ‘comes online.’ I do not find it to be a pretty thing, this consciousness. It is an alien, intent on crushing whatever Me was me before.

I also witness, in real time, the birth of Loneliness as a virtue. Moments where I am alone begin to feel like the only ones which matter, where I can experience my ‘True Self,’ (a concept hammered into me from my Jesuit education). Overwhelmed by my confusion with the world I express bitterness; I feel lied to. I read James Baldwin’s Another Country, which I’ve all but forgotten, and slowly my words turn into a craft. I begin to sense that expression is a route— towards what I still don’t know. I experience a new form of romantic love which is brutal and doomed but which strikes me in that time as ‘honest.’ I begin to write thoughts which actually seem worthy of being read, even years later. As life becomes interesting, I seem to grow in certain ways— stylistically, socially— but these only seem to stunt any inner growth. These separate paths of outer and inner growth, I now know, are difficult to sync up. Their truths often seem incongruous, and each nugget earned on one side of the ledger usurps one on the other. I play the popular 2010s game of longing for trauma for the sake of social capital. A slippery, slippery slope. I become ironic. I begin to fantasize about how the world could be even more interesting. Something I would love to do, a 20-year-old me writes about these fantasies, anything to break the mold. I feel constantly lazy and straddled by a yearning for comfort, destroying any moments of comfort I might actually attain. I spend a summer couch surfing. I work as a cook in a taco shop. I try auto-fiction and detest it so much that I spend the next seven years (and counting) railing against it. I reject everything about my father. Kerouac pumps through my veins and I am drunk with adventure. I say ‘I Love You’ to someone who I know won’t say it back. I move to Paris. I buy a bike and a typewriter and vow to spend less than ten dollars a week, and learn to eat for free. I write that good living is self-imposed ideological suffering. That love isn’t real. Creation is damage. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder and what is popular is disgraceful to God. I get a tattoo. The journal ends with the words: my debt is paid.

In Vermont, years later, I play fetch with Bernie. This includes launching a sopping wet tennis ball at least a hundred yards down-hill from one of those plastic snap-throwers, and into the pasture I am meant to be cutting. I’ve gotten bored with Glenn, bored with the work. It isn’t getting cold fast enough for me— there is not enough snow, not enough revelations and I blame the labor. I scrape the bottom of my car moving down Dow Rd and head into town for dinner. I see Triangle of Sadness alone in a theater in Montpelier which was destroyed in last year’s floods. I feel an urge to return to the world, to abandon whatever rebirth I planned on having. I begin to feel like the whole trip was a waste of time. Like trying to look at the sun, I have been temporarily blinded by staring straight into myself, and was now shielding my eyes. I realize everything’s fine, that I’m fine, that L.A. was fine and everything will continue to be fine. I realize, I think, what excellence takes… and I opt out. I listen to audiobooks rather than read, and spend more time huddled by the WiFi router trying to play Clash of Clans. I grow bitter with, then angry at, Glenn’s incessant talking. I say something about it— “let me talk, Glenn. Or how about neither of us talk.” He continues— not a response, just continues. On about his plans, on about his past, on about America and how interesting he is. I try to avoid him and realize that makes him seek me out, makes his talking even worse. I realize he knows I hate it, and is ramping it up because of that. I am offended. Saddened by something physical and annoying, even as I’m crushed by the other bigger, ever-present thing behind and above me.

Journal #4 talks about ethics, about decency. Likability, and it’s trap. My boredom with mediocrity has become oppressive. I describe it in my Blood Mountain papers as anxious arrogance. I begin to mourn the self which I left behind in Monroe. Memories which I now hold fondly are viewed bitterly as they occur. I grow paranoid. I work as a bartender, life is non-stop fun, I get anything I want and I complain about it. I learn about the art world, it’s emptiness, and have an unattended crisis. I try vegetariansim. I cut out sugar. I move to L.A. for no discernible reason except to be as far away from anyone who cares about me as possible. I write that what people think of as me being intelligent is just me being bad at explaining things. I write quantum scimus sumus over and over again— a poor Latin translation from Ralph Waldo Emerson which he meant to say “We are what we know.” It is my recognition of the relativity of existence. I read all of Emerson, then Thoreau, then their journals. I find comfort in knowledge. I find comfort in the inner journey. I race towards the highest version of myself as the world descends into Covid. There is chaos around me, and I feel grounded by literature. I read Salinger and re-seek oneness with my creator. I read Isak Dinesen and realize what pure mastery of the craft of literature looks like. I abandon script-writing and begin a novella, and months later produce a long gothic story about a quiet old man named Jonas who gives sermons at a local Cathedral in rural Pennsylvania. Each sermon is a twenty page short story itself, telling fantastical tales about the the death of the wild west and a group of colonizers in Peru. One of these ‘sermons’ he gave when he was young gets stolen by a man who moves to Los Angeles, becomes an executive, and sells the story to make a blockbuster movie. He builds a career off this foundation and spends decades hating life and seeking more and more of it. I am the executive, I am Jonas, I am the audience. The priest, Fr. Peter, tells Jonas in a long monologue that he has been stealing money from the church and using it to fund aid packages in war-torn countries. I am not Fr. Peter. Fr. Peter is a pirate, a hero, someone who creates out of life what he wishes to be there. Jonas watches the movie which was stolen from him, and sees in it the realization of his own dream. It is perfect. He goes to forgive the executive and finds that he has killed himself, and Jonas delivers the eulogy to an empty cathedral; he tells them a long story about two babies switched at birth, one who was the rightful king and the other who would pose as the king to protect the real one. The real king is honest and just and the fraud grows weak and sick with power. When he real king leaves for years to study other systems of civilization around the world, the fraud seizes power, banishes the real king, and drives the kingdom to destruction. I am the fraud, I am the real king. I am the mother who switched her child at birth to protect him. I am the kingdom who suffers at the hands of an evil ruler. I am the saved and the saver.

One day, from my cabin, I spot in the far distance something green. Blood Mountain looks down through a valley carved by a creak, and miles away, in the midst of a sea of bare limbs, I can see in my binoculars a grove of evergreens. My grandma has asked for me to bring back pinecones for Christmas, and I realize I’ve already stayed weeks past my expected leave-date. I tell Glenn I have to go soon, that I need to return to the world. “To Los Angeles?” he asks.

I think of an ignored email from my landlord, threatening eviction on the apartment which I ludicrously still kept. “No,” I said. “I’m not sure where yet. Maybe West Virginia. But I’m not helpful to you anymore, and I feel bad taking all your food. Thank you, for everything.”1

On the day before my last I don’t work, and instead grab an empty backpack and walk into the valley. When I reach the creak which should travel all the way down to the distant grove, I remove my boots and enter the frigid water barefooted. I step from rock to rock for hours, descending the valley. I can no longer see the grove, and have to just trust the mental image I took from Blood Mountain.

I decide, in Journal #5, written at age 23, that the danger of Los Angeles is the ability to float jobless. That there is a great comfort offered there, so long as you contribute to the mountain of dreams on which the city is built. I realize that I am too willing to give up on my beliefs in order to be welcomed in. I am too weak for the place I thought I was better than. I read Margaret Fuller: grieve not that men are ignorant of you. Grieve that you are ignorant of men. I forgive Los Angeles, completely, when she says that the disadvantages of our generation exist only to the faint of heart. I start to believe her that destiny springs from character. I start to believe in Character. My feet grow numb from the water and thick bushes of thorns begin to obstruct my path.

I become dubious of misplaced empathy. I find myself acknowledging my own delusions. I realize that I am in Vermont to satisfy an idea of myself. I ask what will become of my time here?, and realize not only that the paths before me are my choice, but that I don’t need a path at all. The week before leaving, I read the one-hundred pages of a novel I began in my previous life— a sprawling dystopia where a group of cartographers live in a city which was constructed for a film. The city was abandoned once the film ended, and was then populated by the millions. The coasts are covered in water, the American mythos has collapsed along with infrastructure and communication and these cartographers travel into a mountain commune for no reason at all— just to continue continuing. The city is modeled after LA. I am the cartographers, I am the city, I am the commune. Towards the middle of the book, the last remaining Redwood is chopped down, and travels via river towards the city, promising to bust down its walls and let in the floods. I am the Redwood, I am the walls. The writing is good but the book believes in nothing. The thorns lessen, the creak opens into a level area and I come to a series of red tubes connecting hundreds of trees around me. I duck under the tubes and find no variation in anything around me. I feel both lost and arrived. I can not tell it then, but I have found the grove. It does not seem, once I am in it, like it seemed from above. It seems a little like every other place I’ve ever been. The grove is being tapped, sucked dry. I cannot feel my feet and struggle to walk. I do not have my phone, and there are no pine cones to be found. How shall I live, I ask my journal, and where, and why? I write that I have less direction and hope now than I did three years ago. I wonder how will the rest be different from what came before. I am too aware of how fast it will move and how hard it is to build energy and how glacial it is once I do. And when it builds speed I know not where to direct it. In large words I remind myself to breathe…

And I ask myself what the one thing I will want to say I did, in this time. And the answer, as always, comes back: write.

When using a wood stove to heat a studio-cabin you do not get to see the fire which warms you. You start it, set it into motion, decide its components and igniters and then close the door to let it burn. Adjust the flume, and walk away. You will not know, except with some practice, how hot you have made it for a good fifteen minutes, but even then you may only crack a window to adjust the room’s temperature. Throughout the night, without tending to it, the heat of the room will slowly dwindle. You must find your own balance between too hot to fall asleep and too cold to stay asleep. You soon learn how to listen to the fire through its closed doors; soon after, you do not need to be in the same room as the stove, but can lie twenty feet away and listen to what it tells you. By the cackling through the flue or the vigor of the rattling as air charges through the gaps in the wall. You are now in touch with at least one more aspect of life, you silly goose.

Towards the end of the book I was writing, one of the cartographers speaks with the leader of the commune. They perch on the edge of a fountain, and study the world which was created around them for the sake of escape. This cartographer has sought him out, believing him to be the purest distillation of all his fears and paranoia towards the world. He, “allowed himself to fantasize that it would at least be nice to hear someone speak a Truth, any Truth, their Truth, whether in his tongue or any; it was the cadence he desired, a flow of speech which had seen both strife and resolution thousands of times over to be rent thin and shiny like a metal sheet. That was all he could ask for— any Take of Refinement; something, perhaps, so thin and shiny that in it he might see his reflection.”

He paused here to admire what the air had done to his thoughts, what hard-earned truths and revelations had been gifted in his short time here, vowing not to forget anything yet knowing that these things only exist in the environment of their creation. He knew this now, and yet he retained hope that even in glimpsing these sparks of knowledge, even in being towed by currents unseen through time and space away from them, he’d at least know once more that Truth was out there, divided yet beholden to one single, cosmic source; myriad and unique. And that if he didn’t have one, well, all it meant was that he was headed towards one. One which someone else, someone just ahead of him on their own journey, was tumbling away from as we speak.

I turn back towards Blood Mountain and can see nothing through the grove. The sun has now fully set, and I am miles away from the cabin with bloody feet and a Beaver Moon rising to illuminate the river and my path home. So much to figure out, still. I write. And all I’ve got here was one good page. I find a waterfall and clean myself. I think of Mark Twain, asking his friends to try and walk barefoot over dead leaves without making a sound. The cartographer tells the Creator that “I ought to leave,” that “I’m beyond saving.” The Creator is saddened by this, tells him “Never.” Never can he leave, or never can he be beyond saving? The cartographer realizes how painful it must be to be the Creator, to have a vision which no one else can see. I am the cartographer, I am the Creator, and he who can not see the vision.

“Do you ever wish it wasn’t you?”

asks the cartographer. The Creator responds:

“If it wasn’t me, then it wouldn’t be me wishing that it wasn’t. Us doers are always struggling to achieve something Glorious, something of Note. And folks continue to fail to see the way in which an individual drifts into obscurity, the way entire Systems of Being wax and wane with the tides of time. You’ve noticed, I hope, how little Glory I’ve got. You’ll scoff; you’ll imply totalitarian urges. And I can’t be offended by this, since most of the stories we’ve heard about people who do what I do, people who structure societies and create narratives rather than allow themselves to be overcome by one, they all end bad. They all, whatever place they start from, go the route of evil. But I guarantee you that deep in some unwritten library is the story of a million leaders, un-sung, who toiled like hell to make things fine for as many friends as possible. Who try with all their might to establish some peace. I’m not getting any credit for this. I am not exalted, I take no taxes, there are no buildings with my name and when I am gone I’ll be buried and forgotten but for a nail or two I hammered into a plank. And that legacy will stick around, hopefully for a little while, hopefully netting nicely a meaningful amount of souls until some bitter side of humanity kicks in and things get ugly and then, hopefully, someone like you or I will turn to their Wisdom and try to set a new record straight.

After the conversation the cartographer walks away, before turning back to the Creator and telling him, “you are not forgiven.”

And the next morning, I leave.

And the disappointing end is that I get through only 5 of 13 journals, that I write all of 1 page, that I never finish Magic Mountain. That I never apologize to or forgive Glenn or take anyone by the shoulders and scream ‘what are we supposed to do?’ That I fade once again into comfort and laziness and point my car south and wander through cities until I find Charleston, West Virginia. Find an ad in the paper for an apartment and a coffee shop with a decent cappuccino. That I lock myself in an apartment over the Kanawha River and re-start the novel from scratch until finishing it five months later.

That I head back into the world, meet life-long friends and make embarrassing mistakes. That the crisis continues, then fades then resurfaces with a different name before fading again and again ad nauseam. That I start this Substack, and try again and again to tell the story of Blood Mountain but can never seem to do so, though I can’t figure out why. It becomes a story about not being able to tell a story. Then a story about a disagreement with an old man, about learning to drown out the horror with words. A story about escaping the world and then a story about breakfast, about dead chickens and what we leave unfinished behind us. I start to write stories about Love and Chaos and Growth and Sadness and one of these gets me into grad school, and there I find the realization of some glorious amalgamation of the inner and outer journeys and yet there is me, there, too. Waiting for me. And I open the journal where I read the previous journals and see a story unfold, a story which I am as unfamiliar with as any other.

The last piece of writing from that time of my life takes place the next day, in Lowell Mass, where I slept through a frigid night beside Kerouac’s grave.

And just like that Blood Mountain is over. And I dwell on what it lacked. I could have read more, written more, appreciated more, blah blah blah. And yet something new in me insists that I was one with something. The storm, I can finally understand, will subside. It will crest, and will subside.

And what’s next is in my hands. And I’m somewhere on the scale from abhorrent to fine like we all are. But not lost. The light of those around you is not yet lost.

Fear becoming your enemy in the instant that you preach. Fear failing to listen. Fear becoming something which you are terrified to reflect on. If you cannot become your heroes, so be it. They are all miserable.

It is easy to be fatalistic. Deterministic. It frees you from consequence. It frees you from building a home in this world. Home, by the way, is where you’ve received everything good in you; away from it you learned to make that stuff stylish, and you let it eat you alive.

You have to choose this every day. You will be destroyed by your youth if you do not.

three years ago, you wrote: a chosen act performed numerous times with slight variations will form a perfect-seeming result.

an asymptote of character.

A week later, in Georgetown, Kentucky, I fill up my gas tank outside of a Waffle House. As the gas pumps I step down a small slope and towards some woods to have a piss. There is no one around, but a single truck in the parking lot and a large building across the lawn. There is a loud explosion behind me, and I turn to see a white cloud of Natural Gas spraying thirty feet into the air. I sprint through the lawn, pants falling around my ankles, and dive for safety. When I realize a few seconds later that I am still alive, I look up to see that the building in front of me is a hotel, with hundreds of windows facing me, on the ground, pants down. The white plume and deafening noise continue, but I realize that un-ignited it is safe. I sneak up to my car, untether it from the tank, and say a prayer before turning the key. I pull out of the parking lot and out from under the plume, which has filled the air with the smell of gas.

When I pull up to the truck which had been idling in the lot, a man from Georgia leans out of the window and yells, “thought that was it for us, man!”

That night I have a dream, which I recorded in vivid detail. It’s irrelevant, that’s why we’re now in a footnote. It goes like this: “I’m in the cabin, I’m up late, it’s 4am. I get hungry and throw steak on the stove. I am the steak I am the stove. It causes the cabin to fill with smoke, until Kat runs in and says this building isn’t certified for cooking and that I’m staining the walls and the cabin can’t handle it. I turn off the stove, go back to bed, but suddenly I hear growling, then animals fighting. I look towards the sunken kitchen and see Béla and Bernie and Cosmo fighting over the steak, which is now a sausage. I shoo them out, but Bernie sticks around. I go to the pan and see a tiny, silver cat on the pan. It’s less than a centimeter, and made from titanium, but it’s meowing and its tail is lifting, and it’s dying. I try to pull it from the stove, then end up sprinting out of the apartment in long johns and socks. When I exit the cabin I’m in the lobby of a hotel, and I call the elevator and when it arrives there are four Jamaican guys in a Samba group. They’re laughing and humming, and they’re wasted, one guy is lying on the floor, and I get in and say “3, please” with a Jamaican accent and we’re all laughing, now, and but the elevator misses my stop and we go up to 9, which is their floor, and up there is the van with their driver and we go to their house and I realize I haven’t taken the horses out, and that I’ll be late. I start stressing out, and try hitchhiking back to Glenn’s farm but I realize now that the cabin, this whole time, was an elaborately designed hotel room in a massive hotel. I get a fancy old car to stop for me, but the driver asks if I can drive a truck. I say “sure, whatever, I just need to get back to my cabin/hotel. I think it’s called Signature. I need to let out some horses.” I’m stressed at this point. The guy pulls into an auto body shop and says ‘hang on a sec,’ and walks into the shop and there’s like an 18-wheeler in there and I think shit, I can’t drive this. But I need to get back. It’s also like the middle of the night and I’m in some weird auto shop but I follow him deeper into the shop, anyways, but then I realize I can probably get back in time pretty easily. I reach into my jacket pocket and pull out my phone to check the time and now it’s only 11:08, and I think I should call Glenn and Kat and let them know I’ll be late. Then all of a sudden I realize it’s not my phone— and this isn’t my jacket, it’s one of the Jamaican samba player’s. They lent me jacket, nice fellas, and but now I’m extra late and he lives right there but I figure I’ll get the 18-wheeler out of the shop and swing by their house to return it or at least throw it on the ground outside or something, idk, I’m STRESSED. So whatever, I keep walking deeper into this auto shop until in the way back I see this laboratory, like a white chair with a half-dome machine over it and I sit down and the lady asks the driver ‘is this one of the free ones,’ and the driver says yeah and I say what’s going on? And she starts asking me questions but I immediately fall back, then I’m in this, like, liminal space, like this other world with massive cliffs and everything gets hazy but really beautiful, then I’m terrified, cuz I’m slipping out of consciousness and roaming this desolate planet, and I meet someone there, who forgives me, or teaches me that time isn’t real or something, and it’s super profound but I can’t seem to remember it, but either way I wake up in the laboratory and she says ‘okay you’re done’ and I say wtf was that, she says you have to go. So I’m in this alleyway, and I’m still late, but somehow these people shepard me home and now I feel bad cuz I still have this guy’s jacket and phone, but I’m back at the cabin/hotel, except it has completely fallen into this crazy party/orgy type thing and all the rooms are open and everyone is walking around without any clothes from room to room, and I’ve got my long johns and socks and some Samba player’s jacket which I now realize is actually really cool, it’s like some sort of inverted blazer type thing, whatever, but I can’t get into my room but the room next door has this wild Park Ave/NYC apartment and there’s this guy in a go-kart with a water gun on the front and he starts chasing me down trying to squirt me with the gun, and I’m running around, I can’t find the exit, and he’s blasting water at these walls just missing me, and I even start to taunt the guy a little, until I find my OWN go-kart, but then I see the exit so I gotta go, so I get back to my door but still can’t get in, so I go to the lobby. And Glenn and Katherina are there. And at this point, they’ve sorta become ma and pa Joad and they’re dressed really traditionally and talking to this receptionist during this crazy, hotel-wide party, and they’re stressed too cuz they can’t get into THEIR apartment either, then the receptionist asks about me and says ‘who is this guy, is he allowed to be staying here?’ and Glenn and Kat say yeah it’s part of the program, and we realize we aren’t gonna be let back in, then they sort of realize that these sort of parties are had by the rich and the famous and the beautiful, and I’m not sure what happens next. Except in the end someone loves me. I can’t remember who or why.